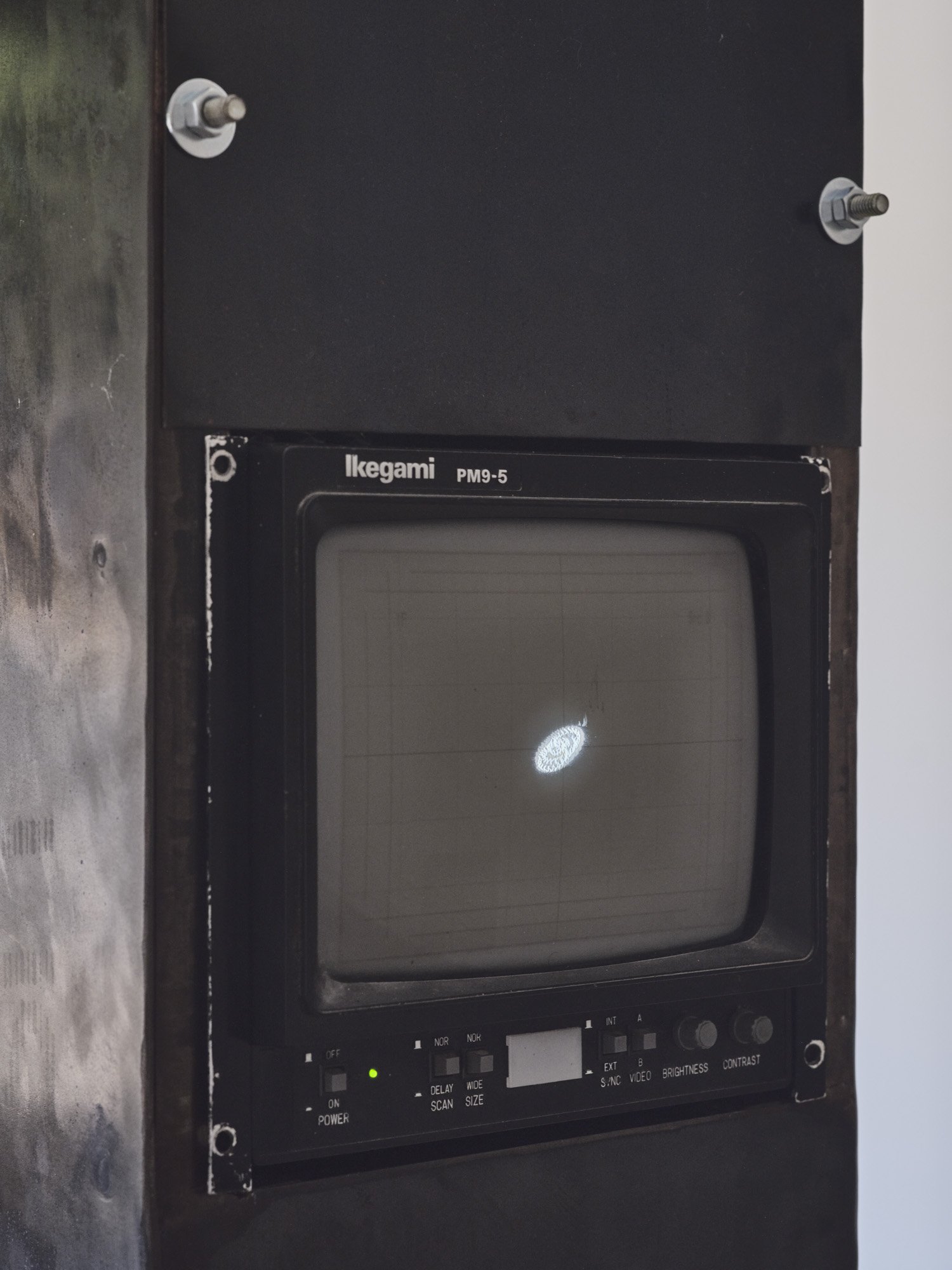

In their book A Thousand Plateaus, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari begin the chapter “How to Make Yourself a Body without Organs” with an illustration of the Dogon egg, an instance of the “world egg” or “cosmic egg,” a cosmogenic motif in which an egg begins the universe. Unlike the teleology implied by “beginning,” however, Deleuze and Guattari write that the “egg is not regressive; on the contrary, it is perfectly contemporary, you always carry it with you as your own milieu of experimentation, your associated milieu.” In other words, neither the chicken nor the egg comes first; they are contemporaries, traveling alongside one another. You are and are with your egg. “Holometabolism,” curated by Mimi Bowman and featuring the work of Isabel Legate and Oshay Green, evokes the form of the egg. Obvious in the oval silk wall works by Legate, the egg also makes an appearance in the tall, seemingly rigid structures by Green. According to the myth, the Dogon egg is crossed by a series of vibrations, a series which transmutes the egg, enabling it to give birth to the universe. Green’s structures are likewise crossed by vibrations: a speaker within one vibrates the tower, making us aware that the steel that comprises it, solid as it may seem, is actually made up of myriad tiny parts, molecules, each shimmering in their own space. The awareness of this ends the heretofore dichotomy between the steel of Green’s work and silk of Legate’s work—one hard, one soft—as both are revealed as simply matter in metamorphosis. “Holometabolism” describes the complete process of metamorphosis an insect undergoes from embryo to imago, pupating in between. One such insect is the silkworm, who makes the silk from which Legate’s wall works are made. The works undergo their own metamorphosis, as well. The oval, evoking Georges Bataille, is also an egg, is also an eye, is also a makeup compact, is also a womb, is also the universe. One zooms in and zooms out, from the micro to the macro: the sun (holo), the stomach (metabolism), the universe, the molecule. Legate’s rectangular forms focus on the macro: zoomed-out images of horizons, the cosmic at work. Green’s work likewise captures movement; his two towers stand as a monument to the fact that sound is always already motion, a series of waves that register in our brains as noise. The towers are separated into the aural and the visual; a speaker in one fills the hollow column with vibratory sound, which travels through the membranous steel to our ears; an oscilloscope in the other visualizes what we hear: sine waves, which round and loop, creating a series of geometric forms. The waves are chosen as much for what they look like as for what they sound like, reshaping our relationship to sound as one that ignites multiple senses, rather than only one: hearing, sight, and touch.

And yet, Green’s work stands—to the naked eye—still, the towers solid and resolute, remaining in their space, shaping the scenography of the gallery. They are a testament to the necessity of foundation for unraveling; in holometabolism, the insect is only able to fully liquefy because it is safe within its chrysalis—it knows it has a shape to fill, that it will not seep out, vulnerable to the outside world. There is also a form to the audio and the oscilloscope; the sine waves repeat every thirty minutes, a kind of hauntology that acknowledges the past form is always extant in the present form, in the future form. But to loop is not necessarily to repeat undifferentiated; to return to Deleuze, difference is always at the heart of repetition; to borrow from Heraclitus, one cannot step into the same river twice.

In “Holometabolism,” the egg—like the chrysalis, like the tower—is not only a form of creation, but one of decreation, as well. “Decreation,” a term coined by Simone Weil, is described by Weil as that which “undo[es] the creature within us,” and later by Anne Carson as the “dislodging of herself from a center where she cannot stay because staying there blocks God.” In the pupal stage, the insect both creates and decreates; indeed, decreation is a form of creation, a kind of becoming to the next stage even as it is also a dislodging, an undoing, an unblocking of God. It is the act of undoing to become, an act that well sums up Legate’s work, both in its form here and in her performance and choreography, as well as Green’s, the sound unfolding into its various parts to create a new experience, the steel breaking into its molecular components.

In the lead-up to this show, Legate read Alejandro Jodorowsky and Marianne Costa’s Way of Tarot. In it, they describe the Tower, an oft-feared card, associated with death and destruction, as a card of “great spiritual comfort,” “not the house of God; it is the House/God.” Green’s towers take on new energy with this reading. Now cue card XXI, another iteration of the House, another iteration of the God: the world, shaped as an oval, an egg. Jodorowsky and Costa continue here, speaking as the world:

The one who becomes entirely pure and concave, who allows me entrance, will begin to dance with me and to say what I say. This individual experiences universal love, complete thought, cosmic desire, and inconceivable life force… Leave behind the herd of your feelings to drown within my infinite exaltation; offer me the demented mob of your desires, so they might enrich, like an exquisite delicacy, my constant creativity… You shall then be master of your world. Inside your libido will no longer be in revolt, your desires will cease to drown you, your thoughts will not destroy you, and your body will pose no obstacle to your life. You will be full and united to me in dance, joy, and immeasurable celebration.

Let go and let God, they say. Let decreation, I add, let creation, let the world, let the tower, let the universe, let the egg.

Text by Grace Sparapani

Photos by Andrea Calo